It has been said that art brings consolation in sorrow and affirmation in joy. This is true not only for those who experience the art but for those who create the art. The creative process, especially literary works, can also have a type of therapeutic and redemptive effect for the writer, who must marshal and articulate those haunting “thoughts which have not yet found expression.” This is the story of one writer who persevered through personal tragedies and despair and gifted us a moving work which still resonates to this day.

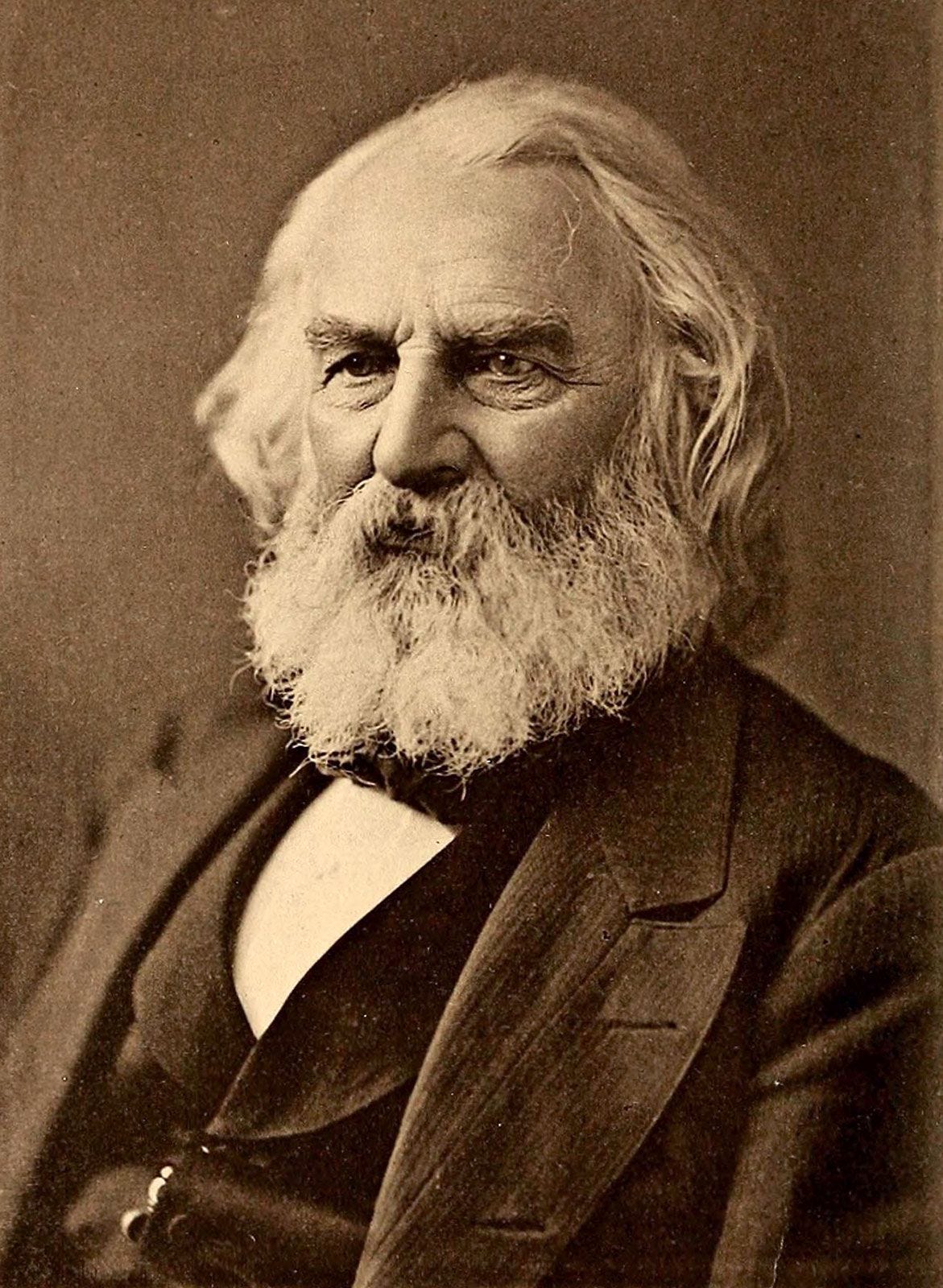

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, the accomplished American author and translator and poet, married his second wife, Frances (Fanny) Appleton in 1843.1 They met in Switzerland through a chance occurrence in the summer of 1836 where both her family and Henry were in the beautiful village of Thun. (Fanny’s father and Henry shared connections to Harvard and Boston.) Henry (who was 29) would stay with, and travel with, the Appletons – and do his best to make a strong impression with Fanny, for whom he had taken an instantaneous liking. His efforts failed initially, as she would describe him as having a “false” and “flimsy” character. Yet he seemed to have at least somewhat charmed her through their travels and shared literary interests and walks through Swedish towns.

This began Henry’s long courtship of Fanny. She wasn’t impressed by his celebrity or smitten his writing or flattered by his interest, and maintained she had no romantic feelings for him. Fanny, after all, was attractive and artistic and well-educated and well-traveled, and had grown accustomed to the courtship of established and prominent suitors – to the point of being bored by some. But Henry persisted, sometimes to his physical and mental detriment, and he eventually made true on his vow “to win her affection.”

Fanny accepted Henry’s marriage proposal in the spring of 1843, and they were married in a candlelight ceremony about a month later. After accepting Henry’s proposal, Fanny wrote her aunt: “How it was gradually brought about you shall hear by and bye, or rather what is there to tell but the old tale that true love is very apt to win its reward.”

Henry and Fanny would have a happy marriage, one which involved travel and improving a home and the delivery of six children. Fanny would also assist with the proofing of Henry’s translations and other works. But there was also tragedy. In 1848, their daughter Fanny died from illness. She was 17 months. After she passed, Henry would describe sitting “by her alone in the darkened library.” Fanny would say she had “a ‘terrible hunger of the heart’ to hold her namesake once again.”

Their family suffered another tragedy in July of 1861. As she was clipping locks of her daughter’s hair, Fanny’s hooped summer dress caught fire. The cause of the fire is not known; the best guesses are that a gust of wind possibly knocked “a burning taper onto Fanny’s lap” or that an “errant drop of molten wax” somehow “ignited the hem or sleeve of her highly flammable dress.”2 Her dress was immediately engulfed in flames and she ran to Henry’s study. After unsuccessful attempts to subdue the flames (which resulted in injuries to his face and hands), Henry was able to finally “snuff out the fire with a small throw rug.”

Fanny would die the next day. Henry was devastated, described as “desolate” and in an almost “raving condition” soon after her death. At her funeral service, the bells in Cambridge tolled in her honor while Henry “remained in seclusion, tending to his bodily wounds and battered psyche.” He lay in bed grieving, questioning why he couldn’t save his wife. His son would recall that Fanny’s death “was a terrible blow to him, from which he never recovered.” Not long after her death, Henry would write of being unable to lift his eyes toward the future and of how his heart was aching and bleeding for their children.

Eighteen years later, Henry would still mourn for his wife, recalling her face and her memory and expressing his lingering anguish in The Cross of Snow:

In the long, sleepless watches of the night,

A gentle face — the face of one long dead —

Looks at me from the wall, where round its head

The night-lamp casts a halo of pale light.

Here in this room she died; and soul more white

Never through martyrdom of fire was led

To its repose; nor can in books be read

The legend of a life more benedight.

There is a mountain in the distant West

That, sun-defying, in its deep ravines

Displays a cross of snow upon its side.

Such is the cross I wear upon my breast

These eighteen years, through all the changing scenes

And seasons, changeless since the day she died.

Nearly two years after Fanny passed, their 18 year-old son Charley left home to join the First Massachusetts Artillery. He did so in secret and informed his father of his plans after the fact:

Dear Papa,

You know for how long a time I have been wanting to go to the war. I have tried hard to resist the temptation of going without your leave but I cannot any longer. I feel it to be my first duty to do what I can for my country and I would willingly lay down my life for it if it would be of any good. God Bless you all.

Yours affectionately,

Charley

Henry, who was politically connected through his prominence and familial relations, helped to arrange Charley’s assignment to the First Massachusetts Cavalry. In June of 1863, not long after his enlistment, Charley fell “grievously ill” with fever. Henry would travel to Washington, D.C. to spend a few weeks at Charley’s bedside, and would write to his son Ernest of hearing “the distant cannonading, mingling in with the sound of the church bells and the chanting of the choir in the church close by.”

Charley would eventually recover from his illness and take part in the Mine Run Campaign, a Union offensive in northern Virginia against General Robert E. Lee that commenced on the morning of November 27, 1863. There, Charley would be severely wounded as described by Henry: “An Enfield bullet passed through both shoulders, just under the shoulder-blades, grazing the back bone, and making a wound a foot long.”

That Christmas, as he was tending to his recovering son and still broken from the death of his wife, Henry took to paper, writing a poem that touched upon his memories of hearing bells as he tended to his sick son and perhaps those that rang at Fanny’s funeral. He expressed a message of hope through death and despair and the ongoing Civil War:

I heard the bells on Christmas Day

Their old, familiar carols play,

And wild and sweet

The words repeat

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!And thought how, as the day had come,

The belfries of all Christendom

Had rolled along

The unbroken song

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!Till ringing, singing on its way,

The world revolved from night to day,

A voice, a chime,

A chant sublime

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!Then from each black, accursed mouth

The cannon thundered in the South,

And with the sound

The carols drowned

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!It was as if an earthquake rent

The hearth-stones of a continent,

And made forlorn

The households born

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!And in despair I bowed my head;

"There is no peace on earth," I said;

"For hate is strong,

And mocks the song

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!"Then pealed the bells more loud and deep:

"God is not dead, nor doth He sleep;

The Wrong shall fail,

The Right prevail,

With peace on earth, good-will to men.”

That poem would become a song and that song would become a classic, a unique carol in the American Christmas catalogue. You may know it best from Frank Sinatra.

Merry Christmas!

-T

All references and quotations herein are attributed to Nicholas A. Basbanes, Cross of Snow: A Life of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

“While decidedly gruesome, Fanny’s accident was by no means an isolated incident. Serious injury and death in this manner was distressingly common during much of the nineteenth century, the fashion for billowy dresses known as crinolines made with highly flammable open-weave fabrics making for a deadly combination.” Nicholas A. Basbanes, Cross of Snow: A Life of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

I so wish more people knew the background of this wonderful Carol especially pastors/ministers who like to chop out verses to sing just the first two or first and last. You don’t get the message of this hymn unless you sing all of it.

What a beautiful story and an important piece of history. Thank you! What a beautiful Christmas present you have given me. This has always moved me deeply and now I know why!