This is the story of how the FBI framed four innocent men for murder, destroyed families, and tried to cover it up. It’s also the story of the convergence of John Durham and Robert Mueller: how Durham uncovered the FBI’s crimes and how Robert Mueller’s FBI disputed the innocence of the men the FBI framed.

The FBI knocked and Mike Albano opened the door. It was 1983. As a member of the Massachusetts State Parole Board, Albano thought he had been doing his job when he looked into voting to commute the sentence of Peter Limone, who along with Joseph Salvati, Henry Tameleo, and Louis Greco, had been convicted for the murder of Teddy Deegan in 1965.

Those convictions never sat right with Albano – he was savvy to Massachusetts and the ties between the Mob and law enforcement. His suspicions of the convictions, and sympathy for the four men, only grew when he met with Greco, who proclaimed his innocence and said “he wanted to live one day as a free man, just one day.”1

FBI special agents John Morris and John Connolly weren’t there just say hello or to discuss the details of the case (a state case, not a federal case). There was a darker purpose: straight-up intimidation. The FBI agents let it be known, in no uncertain terms, that it wouldn’t be good for Albano’s career if he voted for commutation.

To Albano’s credit, he voted to commute the sentence of Limone. This particular petition for commutation (Limone filed six in total that were all rejected) was denied by Governor Michael Dukakis after the FBI and then-U.S. Attorney Bill Weld put on the pressure, alleging that Limone was guilty of the Deegan murder, had been involved in commissioning the murder of Joseph “The Animal” Barboza, and would return with seniority to Boston’s organized crime structure if he was freed.

The Parole Board also voted in favor of two commutation petitions by Greco. The first was denied by Governor Michael Dukakis, the second denied by Governor Bill Weld. There was no ruling on the third commutation petition filed by Greco in 1995. He died soon after it was submitted. Greco’s plea to Albano, that he live “just one day” as a free man, was never granted.

To understand this case and the FBI’s efforts to intimidate Albano, you have to go back to the 1960s. J. Edgar Hoover was the FBI Director and made it a focus of his to take down La Cosa Nostra – the Italian Mob – by any means necessary. To achieve this goal the FBI used criminal informants.

The Teddy Deegan Murder

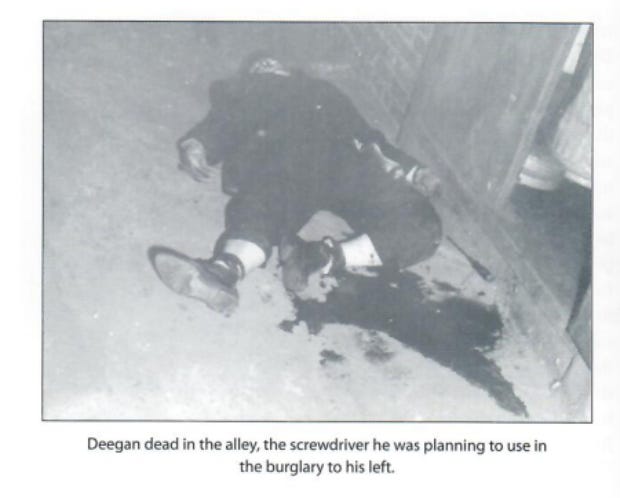

Teddy Deegan was murdered on the night of March 12, 1965 in Chelsea, Massachusetts, just north of Boston. His body was found in an alley behind the Lincoln National Bank. He had on gloves and a screwdriver was found near his left hand. A tool of his trade. The lieutenant who arrived at the scene described a fresh pool of blood near his left knee and blood “still oozing from the rear of his head.” In all, Deegan was shot 6 times with three different guns.

The officers who recognized Deegan there lying in the alley wouldn’t have been surprised. He kept company with hoods and criminals and mobsters, and behaved the part. They didn’t expect Deegan’s murder, but it was always a risk of Deegan’s associations.

Arrests are made.

Four men – Limone, Greco, Salvati, and Tameleo – were accused of Deegan’s murder.

Peter Limone was arrested on October 27, 1967. That was also the day of his tenth wedding anniversary and it was spent in jail away from his wife, Olympia, with whom he had four young children. He was supposed to meet Olympia that evening for a meeting at their sons’ school. He never showed up.

Louis Greco surrendered to the FBI in Miami, having been in Florida at the time of the murder, and was extradited to Massachusetts in 1968. He too was married and had a couple young children. He was also a war hero, having served in the South Pacific in the Army during World War II. He had returned from the war “disabled for life with a shattered ankle.” For his service he had been awarded a Purple Heart and two Bronze Stars.

Joseph Salvati was 34 when he was arrested. Like Limone, he also had four young children. Henry Tameleo was the oldest of the four men. He was born in 1901 and had been married to his wife since 1919.

The Trial and Convictions

The state murder trial started on May 27, 1968. Joseph Barboza, an FBI informant, testified that Limone and Tameleo approved the “hit” on Deegan, that Salvati was there with them, and that Greco helped plan the killing.

Not that Barboza was innocent – he was indicted for a misdemeanor relating to the murder and was serving time for possessing an illegal firearm. This was supposedly part of a deal the FBI gave Barboza: testify for the Massachusetts government in the murder trial and they’d let the judge know the extent and materiality of his assistance. Leniency was a near-certainty.

Anthony Stathopoulos, Jr. had also been at the scene. He testified Greco – or a man who looked like Greco – wanted to get him as well. Other witnesses testified to guilt-indicating conduct by the defendants. For example, it was alleged that Tameleo and Greco tried to bribe Barboza and Stathopoulos to change their testimony.

The defense had an uphill battle. Their lawyers suspected that the FBI might have information or documents relating to the witnesses or Deegan’s murder. But the FBI produced nothing.

The jury reached its verdict on July 31, 1968. The four men were found guilty: Greco for murder in the first degree, Limone and Tameleo for accessories before the fact, Salvati for being an accessory after the fact, and all them for conspiracy to murder Deegan and Stathopoulos.

Limone, Tameleo, and Greco received the death penalty. Salvati was sentenced to life.2 The convictions were brought to the attention of Director Hoover, with the Boston office sending memos citing the Suffolk County District Attorney’s comments that the prosecution was a “direct result of FBI investigation” and witness development.

The FBI agents involved in the case (and who testified in support of their witness) were recommended awards and letters of commendation. They later received large bonuses for their efforts and were even praised by FBI Director Hoover, who was satisfied to see the FBI with the convictions.

The Families

The families of the four men were devastated by the news. They had been distraught since the arrests – but at least with a trial they had hope things would work out in their favor. Now their husbands, their fathers, were facing execution.

It was hard for the wives but the children had it worse. The taunts at school that their father was a murderer. Going through cold prison gates and being frisked just to spend their birthdays with their father. An empty seat at sporting events and recitals. A boy’s nightmares of his father’s electrocution. A girl’s anxiety of missing her dad.

Henry Tameleo was the oldest of the four (aged 66 at the time of imprisonment) and his health was rapidly failing. The prison board and his doctors recommended he be transferred due to his health – these requests were ignored for years. He remained in prison a “sick, lonely old man” struggling with depression. His wife died in 1979. They had been married approximately 60 years; the last 10 years spent apart. He wasn’t there to hold her hand as she passed.

As bad as all of that is – and it is bad – the Greco family took it the worst. Greco and his wife Roberta had two sons (Eddie and Louis Jr.) who were 10 and 12, respectively, when their father was taken away. After Greco’s conviction, his son Eddie – at just 10 years old – contemplated suicide. In his own words, he wanted to “take a plastic bag and kill myself. . . I was putting plastic bags around my head.”

The boys’ mother Roberta stopped cooking and cleaning, and took up drinking and beating the kids. Eddie would go to school hungry. One day in 1970 Eddie came home to find their mother had abandoned them. They lived with family until they were thrown out. Eddie was 13 and Louis Jr. was 15 when they were put out on their own.

Greco’s health suffered the same fate as his family on the outside: deterioration. While Greco (and the other two defendants put on death row) was spared execution due to the termination of the death penalty in Massachusetts, he had always been sentenced to death – it was just a matter of time. His health began failing and he was ultimately unable to do most anything without assistance. He lost control of his bowels and Salvati helped clean up after him. Greco’s right leg was amputated below the knee in 1995 due to gangrene. He died in prison on December 30, 1995.

Approximately two years later his son and namesake, Louis Jr., committed suicide by drinking a can of Drano. His other son Eddie struggled with cocaine and heroin addiction. He would eventually die from a likely overdose.

What the FBI knew.

There were FBI secrets about these convictions for 30+ years. These secrets went all the way up to FBI Director Hoover, and were uncovered in late 2000 by then-Assistant US Attorney John Durham: that the FBI had framed four innocent men for murder. This set-up was “known to, supported by, encouraged, and facilitated by the FBI hierarchy all the way up to the FBI Director.”3

To understand the FBI conspiracy, we have to go back to the 1960s and FBI Director Hoover’s efforts to take down La Cosa Nostra- the Italian Mob – by any means necessary.

Part of that task involved focusing on Raymond Patriarca, a powerful New England organized crime boss. In 1962, the FBI installed a wire in Patriarca’s Providence, New England office without a warrant. The conversations were monitored and forwarded to agents in the FBI’s Boston office. This was kept secret even within the FBI. Per Judge Gertner, “FBI reports describing conversations on the wire referred to it as if it were a human source, an informant just like any other.”

The FBI also made use of informants, with whom their agents were have a secret and long-term relationship. Enter Jimmy Flemmi, a career criminal and top FBI informant. The FBI had known of Flemmi’s criminal history – and knew that Flemmi had been involved in a number of murders. Condon, one of the agents handling Flemmi, had been informed in 1964 and early 1965 that Flemmi had committed several murders. This didn’t matter to FBI Agent Dennis Condon, his Boston FBI supervisor, or even to Director Hoover. He could get close to Patriarca and other mob figures and, therefore, had potential.

Jimmy Flemmi was eventually closed as an informant in the fall of 1965. His brother, Stephen Flemmi, began informing for the FBI not long after. Like Jimmy, Stephen was a career criminal, gangster, and killer.

The FBI’s Knowledge of the Plot to Kill Deegan

The wires and informants against Patricia were well underway by 1965. In October 1964, the FBI learned on two occasions that Jimmy Flemmi wanted to kill Deegan. Director Hoover had been updated on these developments.4

Five months later, in early March 1965, Jimmy Flemmi met with Patriarca and asked for permission to execute Deegan. A couple days later Flemmi returned with Joseph Barboza and asked for the “OK” to kill him. Flemmi thought Deegan was “an arrogant, nasty sneak and should be killed.”5

Two days prior to Deegan’s murder, on March 10, 1965, an informant advised the FBI that Raymond Patriarca, a powerful New England organized crime boss, had ordered a “hit” on Deegan. They had already completed a dry run and “a close associate of Deegan’s has agreed to set him up.” The FBI knew it was coming.

Deegan was executed on March 12, 1965. This was the same day that one of his killers, Jimmy Flemmi, was assigned to be developed as an informant.6

The FBI Protected the Real Killers.

The FBI never doubted who killed Teddy Deegan. The day after the murder, an FBI informant reported that Jimmy Flemmi confessed to the killing along with Roy French, Joseph Romeo Martin, Ronnie Cassesso, and Joseph Barboza. Approximately three months later, Director Hoover was informed that Flemmi had participated in the murder.

The FBI was able to put together exactly how the murder was supposed to go down. After the hit was approved by Patriarca, the men planned to kill Deegan when he and an associate (who was also to be killed) were robbing a place in Chelsea. French was to tip the killers off to the time and location.

Deegan’s death had the criminal world talking. On March 13, 1965 (the day after the murder), a top FBI informant reported that Jimmy Flemmi confessed to murder along with French, Romeo, Martin, Cassesso, and Barboza.

“That account would be repeated over and over with minor variations in every single document the FBI had” before Barboza started cooperating.7 Other accounts supported that theory of the Deegan murder. For example, the Chelsea police had information that the men had been seen leaving a restaurant together at approximately 9 p.m. and returning 45 minutes later. Other informants came forward. Eleven days after Deegan’s murder, on March 23, 1965, it was reported to the FBI that Barboza admitted to the killing. The memo below shows that Director Hoover was informed that the FBI’s own informants had murdered Deegan.

This information wasn’t shared with state authorities or the defense counsel of the accused. As a result, this really became a criminal conspiracy by the FBI hierarchy – all the way up to Director Hoover.

Durham Starts the Bulger Review

In 1995, information of Whitey Bulger’s relationship with corrupt FBI agents became public, leading to an investigation of the FBI’s Boston field office. This included a review of documents relating to Limone’s case.

In late 2000, then-Assistant U.S. Attorney John Durham uncovered FBI memos from the 1960s detailing FBI misconduct in this case, providing them to the DOJ, US Attorney’s Office, the defendants and state prosecutors, and the FBI. As a result, “the Suffolk County District Attorney’s office immediately filed a motion to vacate Limone’s conviction, to grant Limone a new trial, and admit him to bail.

Judge Margaret Hinkle of Suffolk Superior Court ruled that the Durham documents were material, exculpatory, and cast ‘real doubt’ on the justice of Limone’s convictions.”8 The state cases against Salvati and Limone – the only two still alive – were dropped. (Greco and Tameleo had died in prison; their cases were posthumously dropped.)

Mueller

Once Durham uncovered these documents, the Massachusetts Pardon Board reached out to FBI Director Mueller, asking about the FBI’s official response to the exculpatory evidence. The Boston Field Office provided a shameful response that the new evidence of an FBI set-up did not mean that the men were “innocent – it merely means that they are entitled to a new trial.”

The Lawsuit and Aftermath

Eventually, the surviving men and their families, along with the families of the deceased Greco and Tameleo, filed suit against the FBI. Not only did the FBI refuse to admit the truth – that these men were innocent – but the FBI also obstructed their civil rights trial. It turned out that the FBI had been hiding evidence from their own lawyers. This caused Judge Gertner to order that “this matter be brought to the personal attention of the Director of the FBI [Robert Mueller].”

After a bench trial, Judge Gertner concluded this case was “about intentional misconduct, subornation of perjury, conspiracy, the framing of four innocent men.” She awarded the men and their families over $100 million in damages.

For the wrongly convicted and their families, this would never be enough.

Meanwhile, the FBI headquarters is still called the J. Edgar Hoover F.B.I. Building. Mueller enjoys, at least with some, a good reputation despite his small but significant part in this saga. And Durham - now Special Counsel - still quietly looks for the truth.

In this essay, the Author relies in large part on Judge Nancy Gertner’s July 26, 2007 Memorandum and Order in civil action no. 02cv10890, Peter J. Limone, et al., v. United States of America, in the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts.

Barboza pled guilty to conspiracy and had his unrelated charges dismissed. He was sentenced to a year and a day to be served concurrently with the other time he was doing.

Gertner Memo.

Gertner Memo at 49.

Gertner Memo at 12.

Thank you. There's no one like you. I will read anything you write. The detail, the thorough exploration. I knew this story but I still learned something. Thank you for making it seem fresh this many years later.

Excellent historical article and just one of the hundreds of crimes perpetrated by the FBI. Having been in law enforcement for over 50 years, I can recall the days when the FBI agents were authorized for break-ins and/or wiretaps by a memo signed by Hoover. I've never trusted or had any use of the FBI since that day.